From Boat to Bar: How Dick Taylor Chocolate Makes the Best Packaging in the Industry

If you ask Dustin Taylor and Adam Dick, making chocolate isn’t that different from building a boat. “The skills that we learned running a woodshop have really translated to making chocolate,” said Dustin. The best friends and owners of Dick Taylor Chocolate worked as trained carpenters for years, building everything from cabinets to houses in Eureka, California, and even restored a “rusty old sailboat” to working condition and sailed it around the coast.

That is, until they discovered chocolate. Mast Brothers Chocolate, to be exact. And by Mast Brothers Chocolate, they really mean that video the brothers put out in 2010 about sailing cacao beans across the ocean from the Dominican Republic to Brooklyn.

“We weren’t in the food world or anything like that,” Dustin recalled. “It’s more based on the craftsmanship of it. We’d rather build it ourselves than go buy it.”

And build it they have. The two have refurbished elaborate old machines from eBay to streamline their unique chocolate-making process, and their chocolate has won Good Food Awards, International Chocolate Awards, and awards at the Northwest Chocolate Festival, to name just a few.

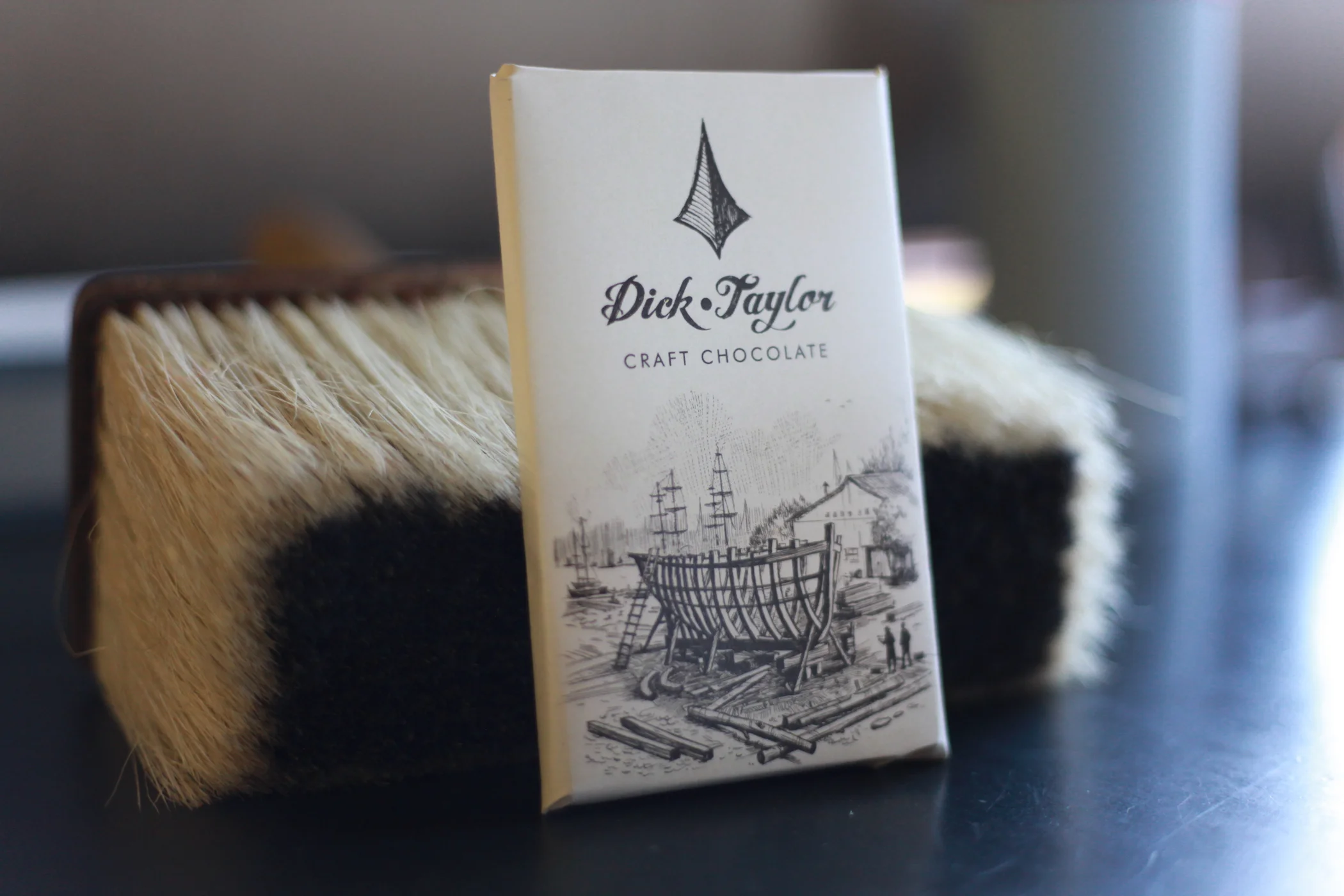

But what really make Dick Taylor Chocolate stand out are their labels. They’ve captured the youthfulness of the new American chocolate movement while maintaining its spirit of simplicity and homegrown attitude, all with images of boats and the sea.

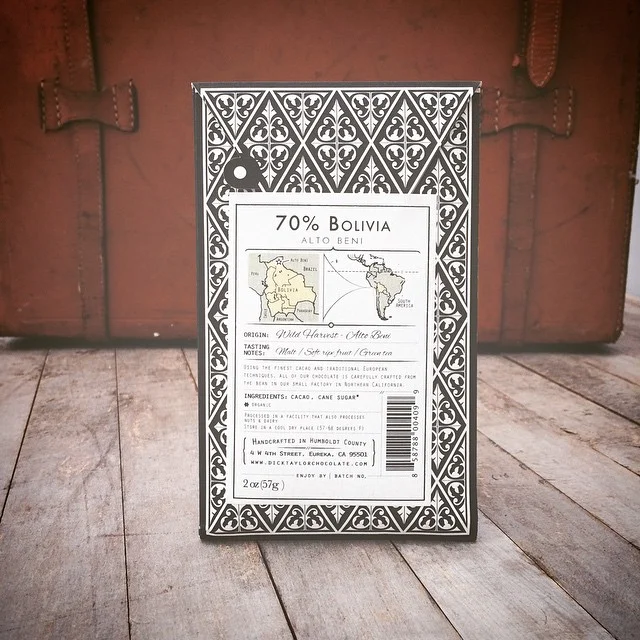

The process hasn’t been easy, though. They started out by simply wrapping bars in beautiful paper like the Mast Brothers do—until they got criticized for it. Time for a new plan. Dustin bought every bean-to-bar chocolate he could find and looked at the labels. “Ninety percent had a brown wrapper,” he said. “Ninety percent were glossy, and a large portion had some kind of cacao pod or Mayan imagery on it. Lots of them are some iteration of the word ‘chocolate’ with X’s and L’s and O’s and C’s—stuff you can’t even pronounce.”

“Okay,” he said. “So we’re going to do everything exactly the opposite of that.”

Starting with the idea of a pattern like “argyle socks” and wood shavings, Dustin reached out to his brother Garrett, a graphic designer and sketch artist who works at Pixar. Boats immediately came into the picture because, well, it’s a huge passion for the guys, who tie it back to the idea that both their boats and chocolate are handcrafted. Garrett decided to go with a streamlined photo illustration in one color (“like the 1890s, but simple,” Garrett said), with two figures in the foreground to provide an anchoring narrative. And on the back? “I wanted that to have more of a utilitarian look so that it felt really approachable, like a box of crackers from the 1930s,” Garrett explained, saying he wanted customers to be able to immediately understand what they were looking at without wading through a lot of text and confusing terms.

Of course, DIY millennials like Adam and Dustin weren’t just going to take Garrett’s designs to Kinko’s. Through Craigslist, they found a foundering print shop in Oakland and loaded up 12,000 pounds of printing equipment at 2 AM one morning, then hauled it back to Eureka, where they taught themselves how to letterpress their own labels. After a few months of letter-pressing and then hand-wrapping the foil and paper around the bars, the guys streamlined once again, creating an envelope that’s easy to open and close, for both them and any late-night chocolate eaters. “I still personally hand-feed all of the envelopes to our letterpress,” Dustin said.

“We want customers to feel like what they have in their hands is valuable,” Garrett explained. “The shape of the package, the thickness of the paper, the feel like it’s worth the $8 or $9 that you spent on it. it’s almost like when you buy like a Mac product, like a new iPhone or iPad. There’s something to the packaging—It’s just a few simple elements that make it feel like whatever is inside is high quality.”

Most impressively, the team has made this happen without spending a ton of money. At the recent Northwest Chocolate Festival in Seattle, makers talked about spending up to $1.50 per package. Dick Taylor, on the other hand, makes it happen for about 30 cents. That’s a huge difference for small businesses who sometimes barely make the bottom line.

Of course, it helps that the guys have done so much of the work themselves, in house. But it’s not like they had experience. “I hadn’t done any type of packaging before for food products, let alone made a mold that would be the shape of the actual food product,” Garrett recalled.

Because it’s not just the outside of the package that matters. To create a seamless experience, they needed to look beyond the paper and the labels, to the actual shape and form of the chocolate. A standard bar of chocolate is usually molded into lots of little squares, so you can easily break off a bite, piece by piece. “But chocolate breaks however it breaks,” Garrett said. “So I started playing around with a diamond shape and just adding detail.” Look at a Dick Taylor bar and you’ll find diamonds on diamonds, with curlicues in the middle of each and a bigger diamond in the center with the words “Dick Taylor Craft Chocolate” and a simplified image of a boat’s sails.

To get the intricate mold to work, Adam and Dustin had to retemper the chocolate almost constantly, as well as play with the liquid’s viscosity in order to get it to set right. “Early on we’d go week after week just tossing whole batches back, just trying to get it to work,” Adam remembered. That threw a huge kink in the process, since if they couldn’t temper and mold bars correctly, they couldn’t very well sell them. A few years later, though they’ve figured it out, and Dustin says that now they only throw about eight bars back per batch of chocolate. Still, that’s quite a commitment for a small company and shows a dedication to high quality and design.

Okay. Chocolate. Boats. Mustaches. The Mast Brothers have already mined this hipster field, and Dick Taylor is doing it again. “We don’t want to be just a cliché,” Garrett said. “The worst thing would be to just follow a trend.” After all, nautical themes are having a moment. That’s why he consciously avoids “throwing an anchor on everything” and focuses on “keeping the sophistication over the easy and quick.” And if the product inside matches the quality on the outside, then there’s no problem, right?

Because let’s get real: Marketing matters. The craft chocolate industry seems to be having a crisis about labels and marketing, with the Fine Chocolate Industry Association and the Northwest Chocolate Festival devoting entire panels and days to helping makers figure out how to best broadcast their message and almost every maker I know is redoing their labels. Industries like craft beer already have whole books devoted to the subject, but a newbie field like bean-to-bar chocolate still has a while to go. At the end of the day, a really good chocolate bar only gets into someone’s mouth if they’re intrigued by the label—or can at least understand the maker’s point of view by looking at it.

And to be fair, anchors aren’t the only thing Garrett avoids. Look at any Dick Taylor merchandise and you won’t see a mustache in site. Well, that’s not strictly true. On the package for single-origin drinking chocolate from Belize, you might find a wrinkly old sailor drinking a mug of chocolate in the rain, sporting a burly beard and a mustache.

“Dustin and Adam embody that hipster feel,” Garrett said. “They both have mustaches, so they want to include mustaches.” He paused, then laughed, “What can I do?”