At the beginning of March I profiled one of my favorite American chocolate makers, Ritual Chocolate. I’d wanted to include some of the fascinating story that co-founder Robbie Stout told me about their conche, but, well, I wanted it in his dynamic words. So for the first time, I’m publishing a guest post on Chocolate Noise. Robbie, take it away!

In 2014 we bought a rusty, dismantled, four-pot longitudinal conche from Steve DeVries [one of the first American bean-to-bar makers, who now acts as an adviser and legend in the industry]. According to Steve, the conche was used by Swiss chocolate company Suchard for around 80 years and then had been hanging out in a barn in Hamburg, Germany, for the past 20 to 30 years. Even when we got it, it was still full of Swiss hay.

When we bought the conche, there was no guarantee that we’d ever be able to get it running, that all the pieces were still there, or that it would even produce good chocolate. So the endeavor to refurbish this conche was a leap of faith—one that was supported by all the old books we read about processing chocolate using turn-of-the-century machines.

For context, here’s a little history. Prior to 1879, there probably wasn’t any great chocolate for eating. Before then, it all would have been a little crude for eating chocolate and was better suited for making hot chocolate drinks. Then, in 1879, Rudolf Sprüngli-Ammann, the founder of Lindt Chocolate, discovered the process of conching after buying an Italian-made machine that looked much like our longitudinal conche. Lindt found that processing chocolate for multiple days in this mixer achieved better texture and better flavor. From then on, Lindt conched all of its chocolate for eating. From about 1879 until about 1900, no one knew how Lindt made its chocolate so smooth, and this is part of where the reputation for smooth, Swiss quality chocolate was born.

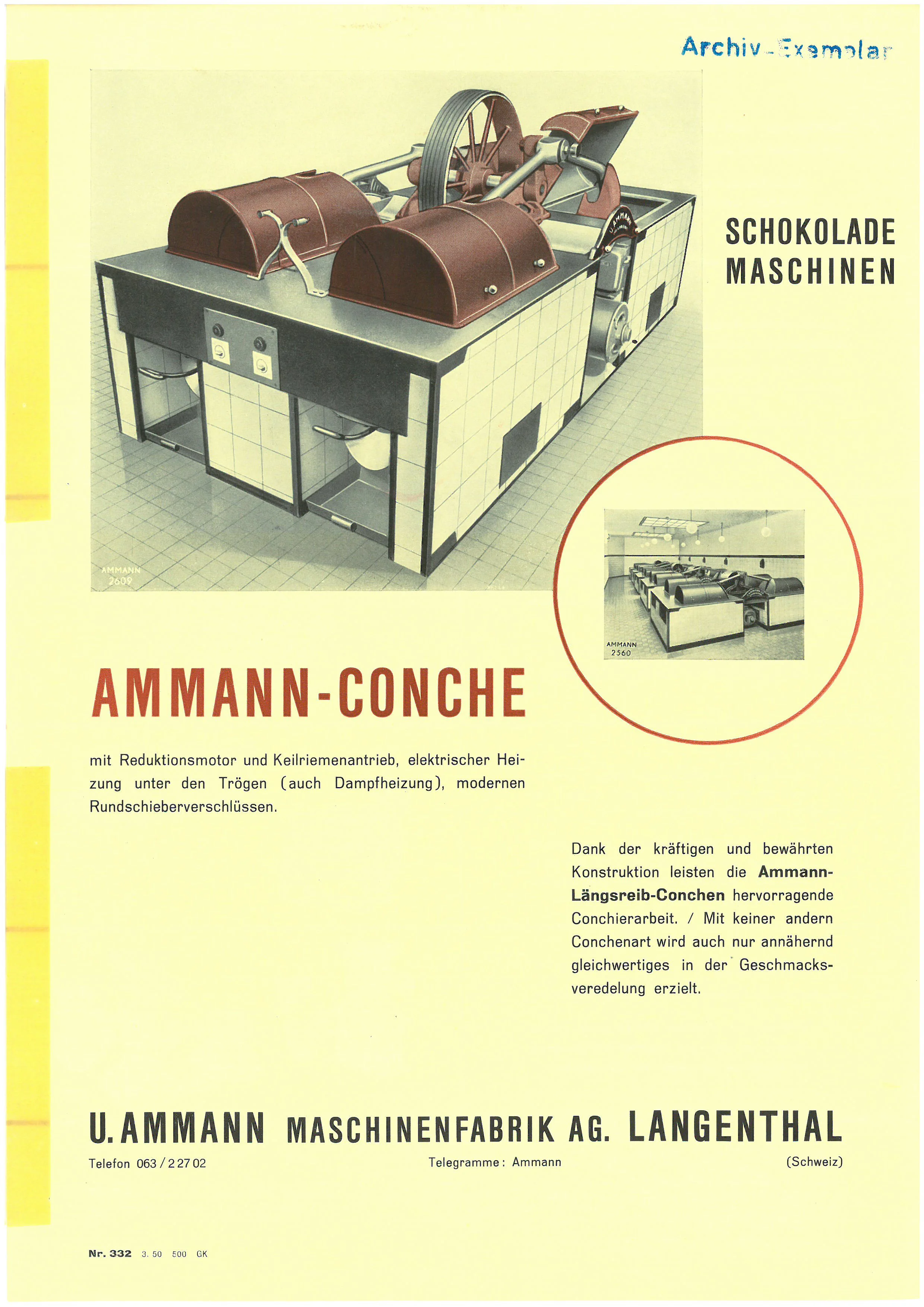

As for our conche, we have a theory that ties into the Lindt conche origin story. Since the early 1800s, there has been a machinery company called Ammann in Langenthal, Switzerland. Originally it was called U. Ammann, and it mostly made farm equipment. Our theory is that when Rudolf Sprüngli-Ammann discovered the conching process, he went to his relative Ulrich Ammann and asked him to secretly produce conches for Lindt. There is no evidence of this, but the time period and the last names align. Also, when Lindt’s secret of conching made it to the light of day, around 1900, U. Ammann was one of the first manufacturers to make conches available to other chocolate makers at the time. Our conche still has the “U. Ammann, Langenthal” insignia.

We had to make several adjustments and changes to get the rusty, old machine to work again. Using old photographs and drawings as our references, we made a stainless steel frame to support all four pots of the conche (back in the day they used brick). We also enlisted the help of Dairy Engineering, a company in Colorado that specializes in “sanitary liquid engineering,” meaning they build a lot of equipment for the dairy and beer brewing industries. The German motor and gear box were built to be operated at a different voltage and electrical frequency, which Dairy Engineering solved by using a variable frequency drive (VFD). Controlling the heat on these machines was also tricky: The engineers used glue-on heaters to heat the outside of each pot and installed a temperature control panel for each individual pot (which is handy for processing different batches of chocolate at a specific temperature).

Initially, they said the refurbishment would take about three months. Instead, it took a full year. This forced us to get creative with our process, but it all worked out okay. Also, when we relocated from Denver to Park City, Utah, we had to move this 15,000-pound, 15-foot-by-8-foot machine with us (an eight-hour drive). We had to hire a trucker to dedicate his entire load to this one delivery (that was expensive). And then to get it off the truck we had to hire a crane, a forklift, and a team to help navigate the conche into our factory.

Once it was in place, electrical installation was easy. The big task was to clean out each pot before use. This took a solid three weeks of elbow grease and a full batch of throwaway chocolate. Last, we had a lot of trouble with the heaters. After burning them all out, we ended up replacing and reinstalling all of them.

Finally, in March 2016, we ran our first batch in the refurbished Swiss conche. That was by far our most stressful batch. There had been so much thought and preparation leading up to this moment, and there was no guarantee things would work out. Per tradition, the first batch would run for three full days. As we had never left the machine alone to do its business, we had to babysit it for the first three nights. This meant setting an alarm for every two hours during the night, walking to the factory (we live close by), and checking temperatures and listening for mechanical problems. Things were mostly fine, except the belt was too loose, so we had to apply a belt dressing during every checkup to silence its screeching.

After three days, it came time to temper and mold our first batch of chocolate from the conche. What we tasted was definitely the best chocolate we’d ever made. The texture was smoother. The flavor was more delicate, yet it lingered longer than it had in the past. And the overall texture of the chocolate felt finer and more consistent. Needless to say, we were greatly relieved. After all the time, effort, and money that went into getting the conche running, imagine how disappointing it would have been if the results had been mediocre!

Since then, we’ve run about twenty 1,000-pound batches. We’ve had to make a few small repairs, but so far it’s running well. If anything, the quality has improved as we’ve been able to perfect the speed and temperature of the conching. Occasionally it can be a little messy, but that’s part of being old fashioned. With the current condition of the granite in each pot, we see no reason why this conche won’t be able to run for another 100 years (or more). And this is why we love old equipment—because it’s built to last.